Interview with Accessible Yoga Part 3: Who Had Access to Yoga in Premodern India

Nov 26, 2018

The Great Stupa at Sanchi. Madhya Pradesh, Stone Relief, (c. 50 BCE- 50 CE).

Image from Diamond (2013, 28).

Part 3/4 of Seth Powell's interview with Patrice Priya Wagner from Accessible Yoga. Reposted with permission. The original post can be found here.

[Priya]

While taking an online course “An Introduction to the History and Philosophy of Yoga” with Seth Powell, I became very curious about the origins of yoga instruction for people who weren’t male and from an upper caste in India—the primary demographic we had studied. When, for example, did people with disabilities, women, or other marginalized groups gain access to the teachings of yoga in India? What allowed for these changes to happen?

Despite Seth's busy schedule of teaching, writing a PhD dissertation, and having a family-life with children, he agreed to an interview to shed some light on these questions. Because the final interview was quite long, with detailed and fascinating answers to each question, I decided to divide it into separate posts, with one question and answer in each post in the series.

Priya: What circumstances in India changed to allow for greater access to yoga—for example, for people with disabilities, of lower castes, and women? Could you explain/describe this for our readers.

Seth: This is very difficult to say. Broadly speaking throughout Indian history, yoga as a discipline was practiced predominantly by a small handful of male ascetics, who retreated from society and devoted themselves religiously to the practice, full-time. Yoga was not viewed as a mainstream activity for cultivating mental, physical, and spiritual health, in the way it is commonly conceived today—both in India and the West. However, at the same time, we should be careful not to view yoga as a singular monolithic, unchanging practice or tradition. There were, and are, many different yogas—plural. With the development of Bhakti, Tantra, and eventually Haṭha Yoga traditions, we can detect the shift from strictly ascetic and initiate traditions, to more public and even householder traditions. In texts from medieval India, we see the proclamation that anybody can engage in the practice. As the fifteenth-century Haṭhapradīpikā (HP), the “Lamp on Haṭha Yoga,” states:

“Whether young, old, very old, diseased, or weak, one who practices untiringly attains success in all yogas.” (HP 1.64)

The Śivayogapradīpikā (ŚYP), the “Lamp on Śiva’s Yoga,” composed around the same time, suggests particular āsanas for individuals according to their station in life. Lotus Posture (ambuja) is for householders. Adepts Pose (siddhāsana) for ascetics. And Comfortable Posture (sukhāsana) is for all others (ŚYP 2.14). From this perspective, it does not really matter which posture one engages, so long as one is able to hold the posture.

Does that mean there was a medieval “Accessible Yoga” movement in premodern India? Not exactly. But for various reasons, the authors of these texts did feel it important to make these teachings “accessible” to a broader demographic, and continually stress their universality. Though we should keep in mind, the texts were still predominantly written in the elite and Brahmanical medium of Sanskrit, which would have limited their audience considerably. It is unlikely that most yogis in India (past or present) would have actually read these texts. Still to this day, among contemporary sādhu and ascetic orders, the oral and spoken word of the living guru is often valued higher than the scriptures (see e.g., Bevilacqua, 2018). And while the texts speak of a growing householder yoga audience, they are still primarily aimed at ascetic yogis.

Why these shifts took place within Indian society and within yoga traditions is still very much discussed and debated by scholars today. Dr. James Mallinson of the Haṭha Yoga Project, the world’s leading authority on medieval yoga texts and traditions, has recently suggested that many of the Haṭha Yoga texts were likely composed within south Indian monasteries (maṭha) and institutions which received heavy patronage during the early second millennium CE.

Within these institutional environments, we can detect a range of issues that were being addressed by the authors of these texts, including who should have access to yoga, and of what kind. There were certainly a variety of prominent yoga systems in parlance during this period, and there was clearly some debate about which was the most effective yoga! The proliferation of yoga styles, schools, and lineages, and debates about “authenticity” and “tradition” is thus not a modern problem—though the discourse certainly looks different today in the face of beer yoga, goat yoga, et al.

We can also detect an important functional shift in the Haṭha Yoga texts in the ways in which the body and bodily posture (āsana) was to be practiced. No longer was āsana employed simply as a “firm and comfortable seat” (as in Yogasūtra 2.46 of Patañjali) used to still the body for breath-control and meditation. In Haṭha Yoga, āsana is used more dynamically to stimulate vital energies within the body (bindu, prāṇa, kuṇḍalinī), and we might even say, “therapeutically.” As Svātmārāma states:

“Āsana is described first because it is the first auxiliary of Haṭha. One should perform it, for āsana [results in] steadiness, freedom from disease, and lightness of body.” (HP 1.17).

Śavāsana, Mayūrāsana, and Kukkuṭāsana. Watercolor illustrations from Richard Schmidt (1908),

Śavāsana, Mayūrāsana, and Kukkuṭāsana. Watercolor illustrations from Richard Schmidt (1908), Fakire und Fakirtum im alten und modernen Indien, Berlin: Hermann Barsdorf.

The Haṭhapradīpikā and other texts describe particular āsanas which are prescribed for specific ailments in the body. For example, the hand-balancing Peacock Pose (mayūrāsana) is said to destroy stomach ailments and diseases, while the famous Corpse Pose (śavāsana) is said to ward off fatigue and bring mental relaxation. I have suggested elsewhere that this shift in theory and praxis seemed to open up new anatomical potentials for the creative ways in which the body was used in Haṭha Yoga practice, and may help to partially explain why we see a surge in the number of āsanas taught in texts after the sixteenth century—as Dr. Jason Birch has recently shown.

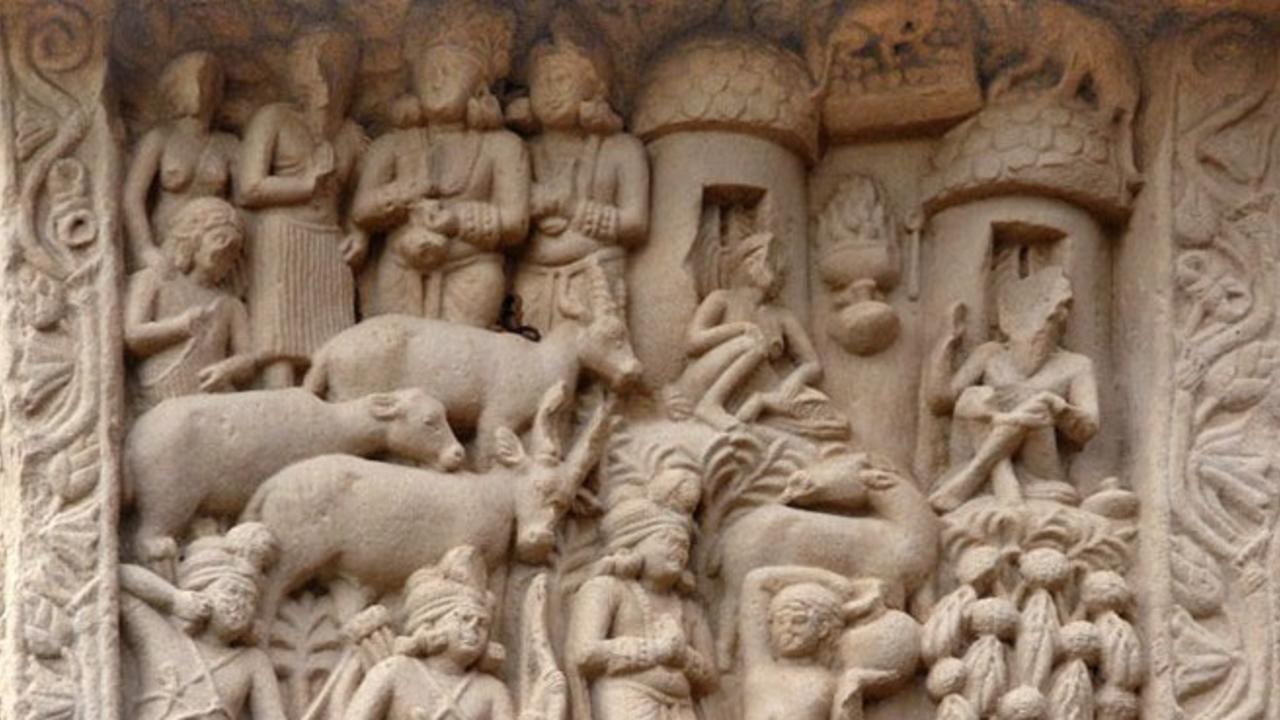

As with contemporary sādhu culture in India today, it seems clear to me that historically Haṭha yogis came from a range of social backgrounds, and were certainly not all of elite Brahmin caste. Recently, at a South Asia conference in Madison, Wisconsin, I heard a great paper given by Jason Schwartz (PhD Candidate, UCSB), who spoke of a very particular lineage of artisan, goldsmith, Śiva yogis in medieval Maharashtra. These were sculptors from what is typically considered a “low caste” who were well versed in both traditional temple-construction arts (śilpaśāstra) and yoga! As scholarship continues to progress on these traditions, we are getting a better idea of who actually had access to the practice of yoga in premodern times.

Birch, Jason. 2018. “The Proliferation of Āsana in Late Mediaeval Yoga Traditions.” In Yoga in Transformation: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives, edited by Karl Baier, Philipp A. Maas, and Karin Preisendanz, 97-171. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht Unipress.

Mallinson, James. 2011. “Haṭha Yoga.” Brill Encyclopedia of Hinduism 3: 770–81.

Powell, Seth. 2017. “Advice on Āsana in the Śivayogapradīpikā.” Guest blogpost for The Luminescent.

Powell, Seth. 2018. “Etched in Stone: Sixteenth-century Visual and Material Evidence of Śaiva Ascetics and Yogis in Complex Non-seated Āsanas at Vijayanagara.” Journal of Yoga Studies (1): 45-106.