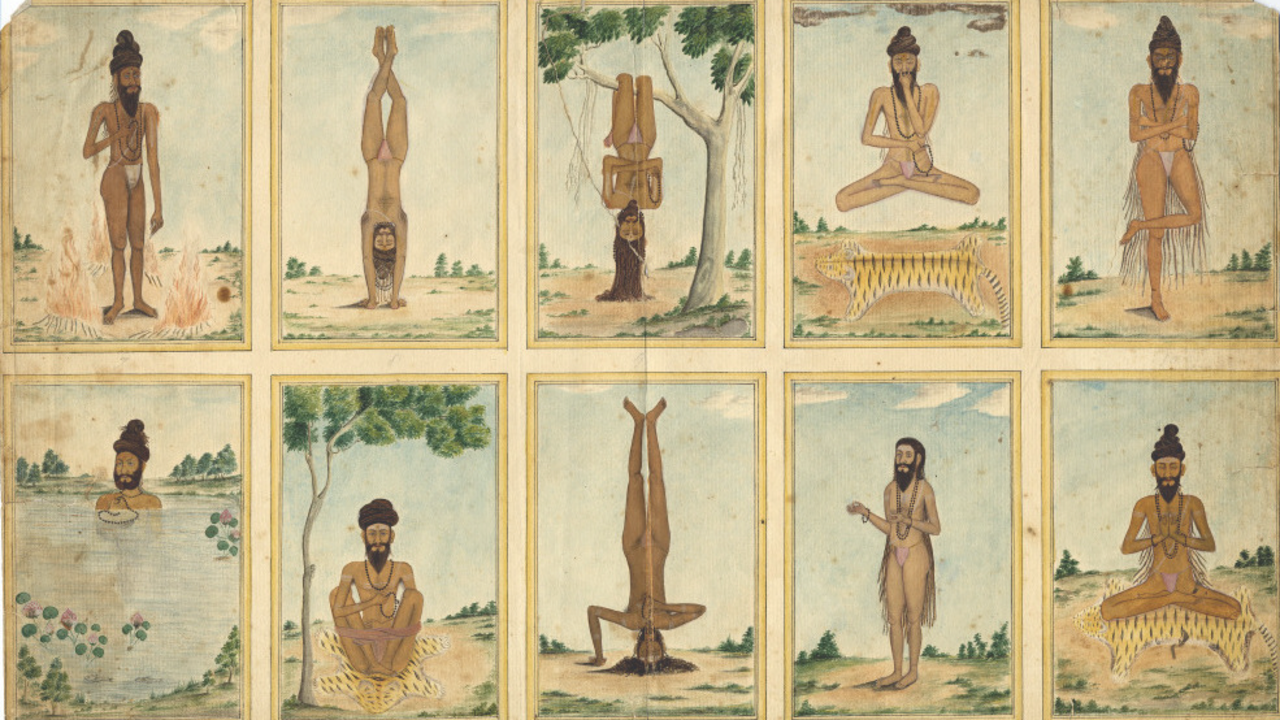

"Ascetics Performing Tapas," South India c. 1820, Opaque watercolor on paper, 23.5 x 29 cm., The British Museum.

Part 1/4 of Seth Powell's interview with Patrice Priya Wagner from Accessible Yoga. Reposted with permission. The original post can be found here.

[Priya]

While taking an online course “

An Introduction to the History and Philosophy of Yoga” with Seth Powell, I became very curious about the origins of yoga instruction for people who weren’t male and from an upper caste in India—the primary demographic we had studied. When, for example, did people with disabilities gain access to the teachings of yoga in India? What about women or other marginalized groups? Despite his busy schedule of teaching, writing a PhD dissertation, and having a family-life with children, Seth Powell agreed to an interview to shed some light on these questions.

Because the final interview was quite long, with detailed and fascinating answers to each question that I asked, I decided to divide it into separate posts, with one question and answer in each post in the series. Here's the first question I asked Seth:

Priya: I’m aware that you're doing extensive research for your PhD on the beginnings of yoga asana practice in India, and I’m curious to know what is the earliest textual evidence we have of people with disabilities gaining access to instruction on asana and meditation practice in India?

Seth: First off, thanks for asking me to do this interview, Priya. That is an interesting question. I’m not sure what the earliest textual moment of this would be. To begin to approach this question though, I think it is important to build some historical context, as you know from my

online courses, I love to do! From the outset, I think we should be cautious in looking to India’s past for obvious justifications for our contemporary social or political ideals and movements. I believe strongly that we should first try to understand Indian history and philosophy—including the early history of yoga—on its own terms. We may discover things do not always align so easily with our own modern concerns and views today, however, this hermeneutic of curiosity and openness can reveal very different ways of being human, in classical and medieval India.

So where do we begin? Most scholars today maintain that the origins of Indic yoga and meditation practices arose out of the confluence of Brahmanical and Śramaṇa (e.g., Buddhist and Jain) traditions, along the Gangetic plain in northern India, sometime around 2,500-3,000 years ago. I think we need to first ask, who were these early yogis?

Broadly speaking, they were male ascetics—celibate, renunciates, on the fringes of early Indian civilization. But they were also “counter-culturalists,” in the sense that they were rejecting and reinterpreting the normative religious and social values and expectations placed upon them by the dominant Vedic society of the day. Many seem to have been Brahmin ritualists or warrior class-men (like the Buddha), who were leaving behind their families, jobs, identities, bank accounts, et al., in radical pursuit of what we now call “enlightenment.” They retreated from society into the forests, banded together in groups, and gathered at the feet of exalted gurus, where they exchanged ideas and practices aimed at eradicating human suffering, overcoming the limitations of the mind-body, in pursuit of great powers, and ultimately “release” (mokṣa) from worldly existence. Hardly the yoga and yogis we think of at the urban studio today.

The origins of postural yoga, or āsana, practice are to be found predominantly among these religious ascetics. Still to this day, traditional Indian ascetics utilize the body to cultivate a certain spiritual power or “heat,” known as tapas. By standing on one leg, or holding the arms over head, for an incredibly long period of time (we’re talking 12 years or more!), the ascetic seeks to gain power over the limitations of the mind-body. For many of these ascetics, often the body is mortified in the process. With the loss of blood flow to the arm, for example, it becomes withered, and rendered dis-abled. This is an extreme form of what we might call an elected disability by choice, wherein one goes to such extreme lengths of cultivating “mind over body” that the body is sacrificed in the process. With the sacrifice of the body, however, comes great yogic power and charisma, and these ascetics are highly revered within their communities. Today we can still see images of these body-mortifying ascetics at a Kumbha Mela festival in India, often used for their “shock” value to exoticize notions of the foreign and mystical East.

In an early Śramaṇa context, the ascetic idea of bodily practice was to completely still the body, in order to no longer produce any karma, which keeps one bound in Samsāra (the cycle of life, death, and rebirth). What better way to cease the production of karma (lit. “action”) than by ceasing to move altogether? We have a famous image of the Jain ascetic Gomateśvara who stood still, stark naked in the forest, for so long that the creeper vines wound up his legs and body, engulfing him entirely as a part of the forest. Elsewhere I have suggested that the much later practice of Tree Pose (vṛkṣāsana), likely develops from this earlier ascetic notion, of “standing like a tree.” The Bhagavad Gītā is famously critical of such an approach, when Krishna tells Arjuna, never for a moment can one not engage in action. Even the renunciation of action is itself a form of action! Standing still like a tree, or sitting like a stone, is still standing and sitting, after all.

Gomateśvara statue, Sravanabelagola, Karnataka. Photograph by Seth Powell.

Śaiva ascetic devotees with

yogapaṭṭas. Ellora (c. 7th century). Photograph by Seth Powell.

Readers may also be interested to note that in order to sit in a seated posture for a prolonged period of time, ancient yogis and ascetics often employed cloth yoga straps! That’s right. This was known as the

yogapaṭṭa in Sanskrit. As I’ve shown in a recent online article, it turns out, the history of the yoga strap is just about as old as the discipline of yoga itself. For more than two thousand years, we might say that yogis have been utilizing “props” to assist their practice (see

The Ancient Yoga Strap: A Brief History of the Yogapaṭṭa).

Okay, but back to your question. While certainly not the earliest textual evidence, one very interesting example that comes to mind of someone with physical disabilities being taught yoga, is the story of Caurangi Nāth. The Nāth yogis were an important Śaiva order associated with the development of bodily-oriented Haṭha Yoga during the medieval period, who trace their lineage to the first two great Nāth (“lords”) Matsyendranāth and his disciple Gorakhnāth. A fourteenth-century text from Andhra Pradesh in Telugu called the Navanāthacaritramu, “The Tales of the Nine Nāths,” is perhaps the first text to narrate the legendary stories, or hagiographies, of nine of these great Nāth adepts (siddha).

Editor’s Note: This interview contains a mythological story with gruesome physical violence that we suggest is to be taken as a metaphor (as we see in the Grimms' Fairy Tales, for example).

The story begins with a young prince named Sāranghadhara who is playing with his pet pigeon while his father, the king, is off hunting in the forest. The bird is enticed by a beautiful parrot and flies off into the private quarters of the prince’s stepmother (one of the king’s many wives). When Sāranghadhara goes to retrieve his prized bird, his stepmother welcomes him and propositions the young prince with sexual advances. He politely declines and leaves, after which his stepmother feels angered and humiliated. Seeking revenge, when the king returns home from his hunt, she falsely accuses the young prince of rape. The enraged king decides that mutilation is the proper punishment for his son, and sends two of his ministers to take the prince to the forest, where they proceed to dismember his arms and legs from his torso. It is a violent, bloody, and unjust scene.

The great yogi Matsyendranāth, who is wandering in the forest, hears the agonizing cries of pain of the prince who was left for dead. Out of compassion, he brings the mutilated prince back to his yogic cave where he nourishes him with milk and care. He then proceeds to instruct the prince in the tradition of Rāja Yoga, through which the prince is able to grow back his limbs, and ultimately attain a “perfected body” (siddha-deha). The prince is thus given the new yogic name, Caurangi, “Four Limbs.”

While there are many disturbing aspects of this violent tale for modern readers, it is interesting to note that the guru teaches the disabled student Rāja Yoga, not Haṭha Yoga. With no arms or legs, the prince simply could not have engaged in the demanding bodily practices of traditional Haṭha Yoga, including āsana, mudrā, and bandha, because it was beyond his physical capacities. Instead, Matsyendranāth teaches according to the inner needs of his student. He instructs the prince in the more contemplative Rāja Yoga, which requires no bodily limbs, but rather through meditation, leads to the spontaneous inner awakening of Samādhi.

This post was edited by Patrice Priya Wagner, co-editor of

Accessible Yoga blog and member of the Board of Directors.

Read the rest of this interview

Further Reading

Mallinson, James and Mark Singleton. 2018. Roots of Yoga. Penguin Classics.

Jones, Jamal Andre. 2018. “A Poetics of Power in Andhra, 1323-1450 CE.” Ph.D. dissertation—University of Chicago.

Gomateśvara statue, Sravanabelagola, Karnataka. Photograph by Seth Powell.

Gomateśvara statue, Sravanabelagola, Karnataka. Photograph by Seth Powell. Śaiva ascetic devotees with yogapaṭṭas. Ellora (c. 7th century). Photograph by Seth Powell.

Śaiva ascetic devotees with yogapaṭṭas. Ellora (c. 7th century). Photograph by Seth Powell.